Texas Highways Hits Wild Coast in van named Janis

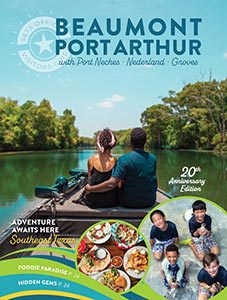

Texas Highways: The Best of the Texas Coast

When “Texas Highways” writers hit Sea Rim State Park in a van called Janis, this was their greeting:

“Honey, there is no place in this park that isn’t pretty,” a silver-haired ranger told me when I ask where’s the prettiest spot for the sunset. “But I’d just park there at the boardwalk by the ocean. Watch out, it’s going to rain soon.”

Read about their epic road trip, then plan your own, to include Port Arthur! Here’s the “Best of the Coast” feature from Clayton Maxwell, with photographs by Kenny Braun, from the June issue of Texas Highways:

Hit the Road

While that ’70s hit song is not included in the cassette tape library that David provides (Led Zeppelin 1 and Willie and Family are) “Slow Ride” seems a fitting motto for our adventure. Yes, Janis is old: You must roll down her windows with a handle and lock her doors with an actual key; her heft and lack of technology impose a mandatory slowing down, one that feels just right.

Sea Grass and Bayous

And, with a warm farewell to David and our families, we are off, eager to hit Sea Rim State Park, the uppermost Texas beach easily accessible to the public, before dark. After listening to Willie and Family for the entire five hours it takes to get there, we pull up to the check-in booth at Sea Rim.

“Honey, there is no place in this park that isn’t pretty,” a silver-haired ranger told me when I ask where’s the prettiest spot for the sunset. “But I’d just park there at the boardwalk by the ocean. Watch out, it’s going to rain soon.”

Who cares about rain? Like a South Padre sea turtle, we have our home with us. We park Janis just as the lowering sun sets the sea grass and bayous aglow. We almost run down to the beach, giddy to feel the waves, which are churning and reddish. Here, at the top of the Texas coast, while the clouds take on underbellies of rain-threatening gray, I realize I’ve never seen an ocean with such a maroon hue. It evokes the shrimp and gumbo I hope to be eating soon since we’d skipped lunch.

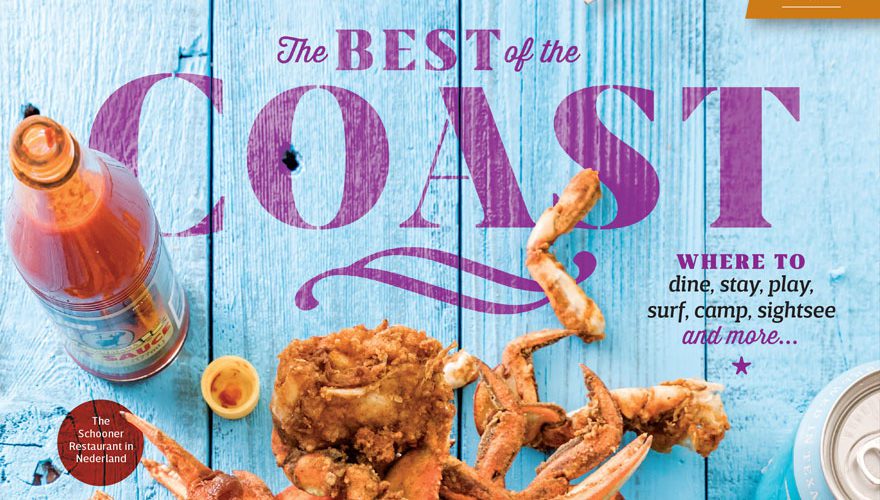

Dinner is Calling

Yes, dinner is calling, and the Stingaree Restaurant overlooking the intracoastal channel on Bolivar’s East Bay is our next stop. To get to the Bolivar peninsula, which is named for the liberator of Latin America Simón Bolívar and pronounced locally as BALL-i-ver—we loop back past the futuristic landscapes of oil refineries around Port Arthur we’d passed on our way to Sea Rim. The juxtaposition of wild nature against steely industry reminds me of another phrase of Blackburn’s: “The Texas Coast is a working coast.” From our window at the Stingaree, we can make out the shadowy images of tankers passing on the ship canal in the dark, giants on the water. Cody, our friendly waitress, brings us the gumbo and the boudain balls I’d been craving since Port Arthur.

And finally, just as the park ranger had warned, the rain comes. Hard. Undeterred, we tell Cody that we’ll be sleeping on the beach anyway. She tells us about the time it rained so much that trucks parked on the beach overnight floated away. Ok, maybe not. With guidance from Cody, we park Janis at Paula’s Vineyard RV park, a haven on dry land managed by Cody’s friend Ruby. After huddling in Janis’ cozy living room, rain pounding, we doze off—Kenny on the fold out bed below, Amy and I in the pop-up top angling from Janis’ roof that shakes in the wind.

The Wake Up

Waking up in an RV park on the Bolivar peninsula is a far friendlier affair than I could have anticipated. As I fumble to find the French Press, a smiling, boots-and-Wranglers-clad fellow approaches the open side door of the van. “Yall just cruising around and sleeping in this thing?” he asks, a hint of envy in his voice. “I used to travel all over Texas, too. I am a retired rodeo man. Can I get you some coffee?” I bought a Keurig at the big H-E-B up in Bay City. You’ll like the San Antonio Blend.”

Next thing I know, I’m having coffee in my pajamas with Ruby’s husband, Jeff, who’d come to Bolivar for the slower pace after a hard-driving life on the rodeo circuit. He tells us that Bolivar is more his speed than Galveston, a short ferry ride away. “We follow island time around here,” he explains, “and you know what the motto is at the Big Store here? If we ain’t got it, you don’t need it.”

What Janis Has Got

That is how we feel about Janis: If she ain’t got it, we don’t need it. From tiny freezer to comfy couch, we love all that she does have. Particularly the cassette player. As we say goodbye to Jeff and the RV park, wheeling past Bolivar’s pastel stilted houses, Kenny pulls out a mixed tape from the ’90s he’d titled Summer Nap, the contents of which he’d long forgotten. As the old cassette kicks in, we get a Wilco’s California Stars followed by John Lee Hooker crooning, “I messed around and fell in love.” Janis lets us travel in more ways than one.

We load Janis onto the Galveston-Port Bolivar Ferry where we catch glimpses of smooth-gliding dolphins, a sight that makes you gasp no matter how often you see it. Once in Galveston, on a tip from a couple of shaggy-bearded pirate guys we met at a taco stand, we make a quick stop at the Poop Deck on the Seawall. With its ocean view and multiple renderings of bare breasted mermaids, we can see why pirates would feel at home at the Poop Deck. We vow to return.

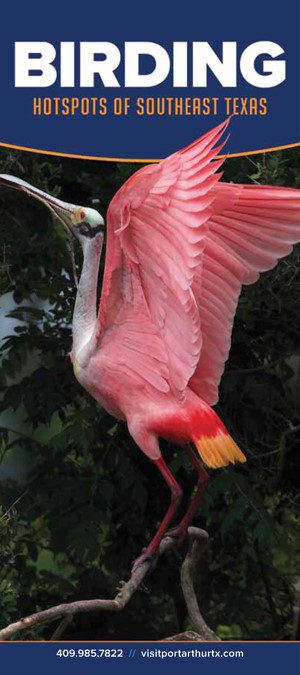

Bottomlands and Brown Pelicans

We steer Janis down coast for an afternoon date with a marine ecologist named Bill Balboa in Palacios, a quiet town on Matagorda Bay and home of a burgeoning coastal conservation movement. From the Galveston Seawall to Surfside, the road is a graceful 40 miles of ocean on one side and sand flats and marsh on the other. Cruising the well-named Blue Water Highway, we race fat brown pelicans gliding low across the sky. We turn inland onto FM 521 and enter the Columbia Bottomlands of Brazoria County. Green farmland and moss-draped oak trees make this country feel more Old South than sand and surf. Swoosh, a flock of slender birds rises like fluttering white sheets from a water-soaked field. Ibises maybe?

“Yes, those were ibises. You were driving past Herf Cornelius’s crawfish farm,” Balboa tells us later, sitting around a dining table at the cozy Peaceful Pelican Bed and Breakfast in Palacios. Apparently, ibises like crawfish. Balboa, director of the Matagorda Bay Foundation, ably translates the language of this rich landscape, one that he and an active group of bay-lovers, birders and fishermen around Matagorda Bay are working to keep alive. They are an enthusiastic, upbeat crew: Laurie Beck, founder of Palacios’ annual Birdfest festival; Paula Whitney who runs the Peaceful Pelican; her friend Cathy Wakefield, a retired Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologist, and others. They come in and out of this charming Victorian house, familiar friends who talk about plankton, spartina grass, and gill nets like we might talk about bands or UT football in Austin.

Fish Nerds

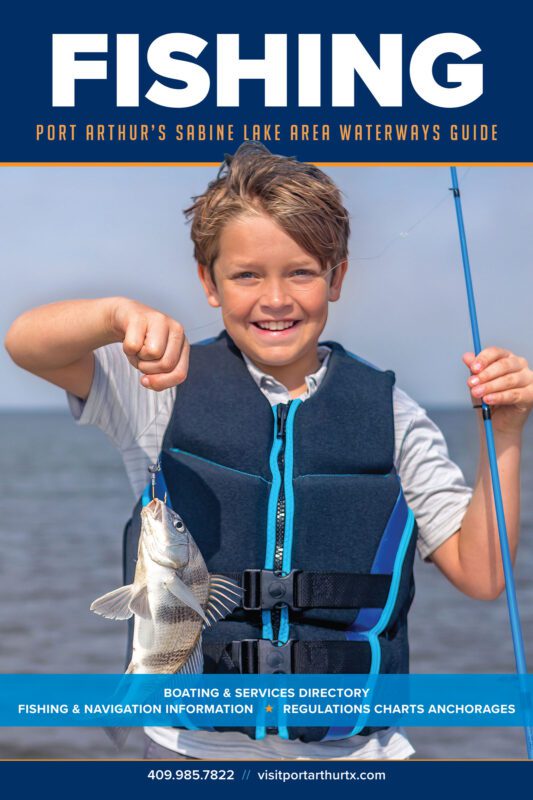

Balboa is pumped about what he found in his gill net this morning. As part of a fish population count in the bay, Balboa checks his nets daily to see what washes up overnight. “Today we found two green sea turtles and a fish called a snook, which is a Florida game fish,” he says. “You just don’t see them here often. When you’re a fish nerd, odd things make you happy.”

Fish nerdiness, we are finding, is widespread along the coast, and it’s the fish nerds who have the know-how and gumption to keep the sea creatures—and economies that depend upon them—happy. “Everywhere you look there are these little ecosystems,” Balboa says, beaming like a kid. “Like on the beach, the yellow seaweed that washes up in the spring? Sargassum. It pisses everybody off. But there’s a whole ecosystem that lives in it. I’m intrigued by how all these things link together to sustain the bay, the marsh, the oysters, the shrimp.”

Balboa also explains the reddish color I saw in the waves at Sea Rim: It’s the result of north winds churning the blood-red silt washed down from East Texas rivers by recent rains. I will never again consider Texas’ rivers and its coast to be two separate geographies.

Between the conversation with Balboa and a delicious visit to the Point, a Vietnamese/Mexican restaurant where owners Yen and Bryan Tran tell us about leaving Vietnam after the fall of Saigon, our heads and bellies are full. I would like to tell you that we braved another blustery night in Janis, but we couldn’t turn down Paula’s kind offer to sleep in the cushy beds at the Pelican, where she and her friend Cathy make us a perfect frittata for breakfast the next morning.

A Delightful Melding

We motor down State Highway 35, an easy ribbon of road that crosses Lavaca and Copano Bays, and into Rockport—more specifically to the home art studio of Steve Russell, a painter whom local fishing guide JT Van Zandt had told me about. What Van Zandt didn’t mention, but we discover as soon as Russell greets us, is that he also looks like a cross between Santa Claus and a grizzly and gives big hugs when you meet him for the first time “He’s a Smithsonian type guy,” Van Zandt had told me. “He used to build flat-bottom sail boats with his dad—that life that no longer exists, he lived it. On top of that, he is a world-renowned oil painter of the Gulf Coast—shrimp boats on rough seas with birds all around. He’s one of the last of his kind.”

Russell is the only surviving founder of the Rock Port Art Center, a group that is still the bedrock of the thriving Rockport Art scene, even after Hurricane Harvey blew its building away in 2017. Kenny, Amy, and I settle into Russell’s living room, its walls covered with his paintings, and Steve, a magnetic raconteur, takes us on a story-telling ride. His tales flow from a life worthy of a documentary, like his days in Mexico after the Vietnam War painting “thousands of Jesus and Elvis” on black velvet.

One afternoon with Russell and it becomes clear that he is a virtuoso who can make just about anything he decides to: carve a violin out of Texas mesquite wood or build an adobe house where he and his friends held poetry readings until Hurricane Harvey knocked it down. His studio—with stacks of books, a large stuffed bear standing on its hind legs, and chandeliers made of glass he blew himself—is a physical manifestation of a mind that never stops churning out fresh wild ideas.

Russell and his wife, Sherol, are on a quest to show us Rockport before dark. They zip us along Aransas Bay, where we stop by a live oak grove, sideways-slanted from the southeast winds, to watch an osprey wading in big puddles left from the recent rains. We pause at a harbor filled with trawlers and shrimpers, and Russell points out the difference between Louisiana luggers and the Texas shrimp boats. I ask him what makes the Texas coast different from others, and his reply is a reminder that, as Blackburn says, the Texas coast is a working coast—a place of shrimpers and hard-knock beer joints—not just a tourist attraction. “Also, the Texas coast is sort of like the Mediterranean with the different cultures,” he says. “Here we have the influence from Louisiana coming over with their own boats and seafood, and the Mexican influence, too. It’s a delightful melding.”

Rays and Waves

Kenny, Amy, and I wake up the next day in a place that feels far removed from shrimpers and beer joints: Padre Island National Seashore. It’s hard to imagine that Janis could ever look better than she does right now, bathed in morning light on the longest undeveloped barrier island in the world—proof that sometimes the best thing you can do is just leave a place alone. I sit on a blanket and watch the sun rise, coffee cup in hand, skin tingling as the first rays hit me. Five-inch clam shells, pinkish beige with gray ridged fans, blanket the sand and shimmer in the horizontal light. There are so many of these shapely beauties on the beach that it is impossible to steer Janis through them without casualties, and we wince whenever one crunches under her tires.

From the seashore, we motor three hours down Highway 77 through the scrubby ranchlands of South Texas to our last stop: South Padre. Amy and I’d made a deal that we wouldn’t go home without catching a wave. As our final act in this trip, we meet up for a lesson with Rachel and Gene Gore of South Padre Surf Co. These surfers have a singular perspective on the coast: In 2004, they paddled the state’s entire coastline over 19 days on surfboards.

“This place is a hidden treasure,” Rachel says, looking out over the blue waves on this island where she’s lived for 17 years. “The whole Texas coast gets some surf, but here we are open to all of the different swell directions, so there’s no comparison. And depending on how the wind is blowing, the water can get crystal clear, like the Caribbean.”

Before our lesson, we watch Rachel and Gene’s yellow retriever surf; he does it backwards, tail towards the beach. The smiling dog makes it look easy. Amy and I both manage to pop up, and time stops as we are caught in the rush of riding a wave. I can see why Rachel and Gene would build their lives around this.

Last Night

Our last night in Janis is a beach bonfire celebration surrounded by the wind-sculpted dunes and bright stars, a few streaking over the ocean as they fall. It’s an exquisite freedom. I wake early, stripes of light peeking through Janis’ curtains. Still in my sleeping bag, I watch a great blue heron high-stepping along the waves. The heron lingers, watchful, as if he were waiting for us to wake up and give him a treat. It can hardly be better than this, I think, admiring the funny bird and grateful to Janis for letting us be eye to eye with this wild coastline.

We head to Manuel’s in Port Isabel for a breakfast feast of bistec and chorizo tacos on enormous house-made tortillas, and talk to Manuel’s son, Frank, who looks out the window at Janis and asks, with a wistful tone much like Jeff the rodeo man way back in Bolivar, “Are y’all driving around and sleeping in that thing?”

Yes, yes we are.